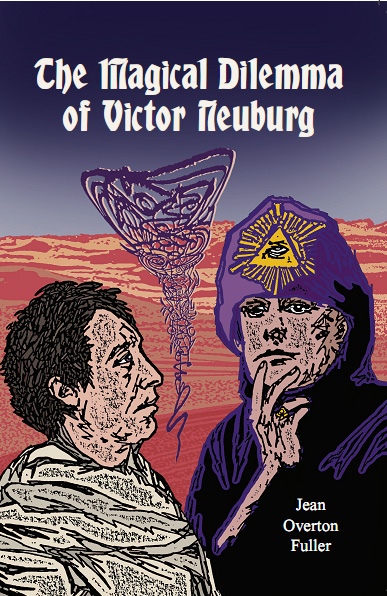

Jean Overton Fuller

(Magical Biography)

The Magical Dilemma of Victor Neuburg

The Magical Dilemma of Victor Neuburg

Jean Overton Fuller

Format: Softcover

ISBN:

£15.00 / US$24.00

Subjects: Biography/Aleister Crowley/Thelema/Magick.

The Magical Dilemma of Victor Neuburg is really two books in one:

The record of Victor Neuburg’s extraordinary journey to magical enlightenment. And the story of Aleister Crowley, the magus who summoned Neuburg to join

him in his quest.

‘The book opens with the author’s entry into the group of young poets including Dylan Thomas and Pamela Hansford Johnson. They gather around Victor Newburg in 1935 when he is the poetry editor of the Sunday Referee. Gradually the author becomes aware of his strange and sinister past, in which Neuburg was associated in magick with Aleister Crowley.

Contents: Beginnings / Mystic of the Agnostic Journal / Crowley and the Golden Dawn / Initiation / Magical Retirement / Equinox and Algeria / Rites of Eleusis / Triumph of Pan / Desert / Triangles / Moon Above the Tower / Templars and the Tradition of Sheikh El Djebel / Paris Working / The Sanctuary / Arcanum Arcanorum / Dylan Thomas

‘Those interested in Western occult history will welcome this revised and expanded edition of an important work first published in 1965.

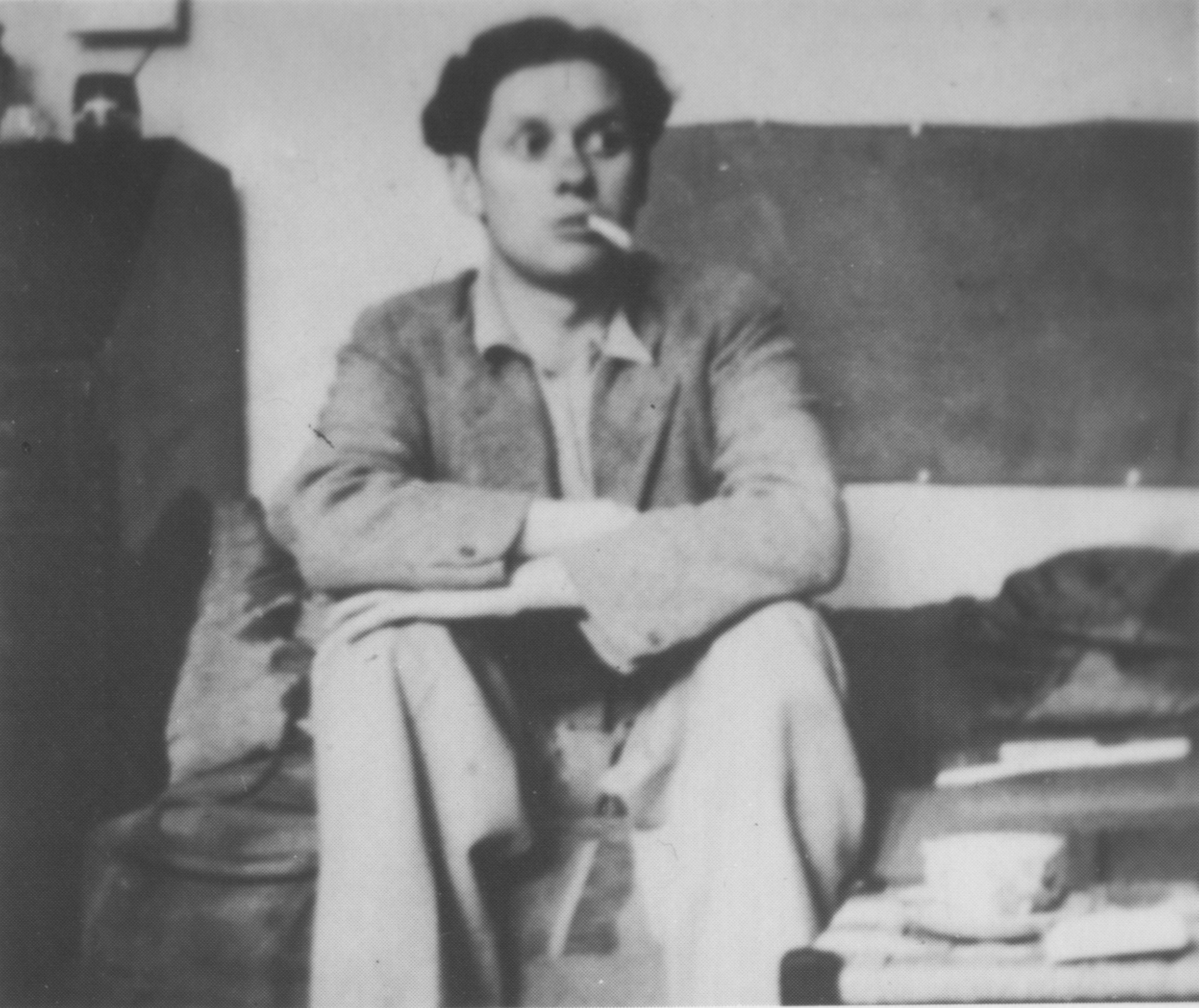

Overton Fuller’s biography of Neuburg paints an intimate portrait of this complex character who was as much mystic as poet. A prominent figure in London’s literary bohemia in the 1930s, Neuburg encouraged such writers as Dylan Thomas, Pamela Hansford Johnson, Hugo Manning and many others, including Overton Fuller.

In his earlier days, Neuburg had been a disciple, magical partner and possibly even lover of Aleister Crowley during a period of ground-breaking magical experiments.

‘Vicky encouraged me as no one else has done,’ Dylan Thomas declared on hearing of Neuburg’s death. ‘He possessed many kinds of genius, and not the least was his genius for drawing to himself, by his wisdom, graveness, great humour and innocence, a feeling of trust and love, that won’t ever be forgotten.’ ‘ . . . there was a whiff of sulphur abroad, and all of us would have liked to know the truth of the Aleister Crowley’s legends, the truth of the witch-like baroness called Cremers, the abandonment of Neuburg in the desert.’

– Pamela Hansford Johnson

‘No dry biography this but an illuminating and compelling account of a multi-faceted personality who lived during an exciting period of occult and literary history. An absolute must-have!’

– (ME) In Prediction Magazine November 2005

—————————–

To mark the centenary of Dylan Thomas, here’s an extract from JOF’s book that narrates her first meeting with the soon-to-be-famous poet:

“We agreed to Zoists”: Dylan Thomas & the Occultist Victor Neuburg (Aleister Crowley’s lover & collaborator)

“We agreed to Zoists.

Runia wanted us to have badges, ‘so that one Zoist can recognize another, if you meet outside, or if we have provincial centres.’

There was a murmur of dissent. Some of us felt this thing was getting inflated. And we didn’t want badges. We weren’t boy scouts; just a few people who wanted to come here and sit and talk to each other on Saturday evenings.

‘All right, no badges,’ she said. ‘But it is agreed we have a name?’

It was agreed but there was no enthusiasm for the name, our feeling being for the informal. Before we left Runia made us cups of tea.

When eventually we broke up, and I stood again in the road outside, I felt I could tell my mother I had been among distinguished people. But the truth was I felt something else as well. I felt I had been in ancient Egypt and for this feeling I could find no explanation.

Not all of those who had been present on the first evening returned the following Saturday, but as I attended every week I began to know the regulars. Arriving soon after 8 (dinner at the hotel where my mother and I lived, was at 7, so it was a rush), I always found a certain number of people there already, though there was usually some time to wait until Vicky and Runia came from the inner room. It was in this waiting time that I had to find my feet, as it were among the other young ones. Nobody was ever introduced at Vicky’s. One just found out for oneself. I did not find the young men easy although they made efforts to draw me into the circle, for they assumed an acquaintance with modern poetry and political authors greater than I possessed; I could not always follow their allusions, and I had the feeling they all participated in a form of culture slightly strange to me. I was therefore grateful when a good looking young man, quiet mannered and of a more ordinarily civilized demeanour, settled himself beside me and asked, simply, ‘How did you come to Vicky’s?’

I told him about the circular letter I had received. He knew Geoffrey Lloyd had sent some out and asked, ‘What do you do when you’re not writing poems for Vicky? What’s your background, so to speak?’

I told him I had been on the stage since I was seventeen.

He said ‘Fancy our having an actress among us!’

‘What’s your name?’ I asked him.

‘William Thomas’, was what I first thought he said, but then he added, ‘It’s a special Welsh name.’

There could be nothing very special about William, and I puckered my brows.

‘You’ll never have heard it before,’ he said. ‘Nobody in England ever has. It should really be pronounced Wullam, in Welsh.’ Or was he saying ‘Dullan’?

‘It’s a special Welsh name,’ he repeated. ‘I shall have to spell it for you. D-Y-L-A-N. In Wales, it’s pronounced Dullan. But I’d been corresponding with Vicky for some time before I came to London, and when I arrived I found he had been calling me Dillan, in his mind. I thought if Vicky didn’t know how to pronounce it nobody in England would, so I decided to take it as the standard English pronunciation of my name. Otherwise I’d spend all my time telling people it was Dull and not Dill, and I think perhaps Dillan sounds more elegant than Dullan. Only Idris objects and thinks it’s frightfully fancy! Because he’s Welsh, too, and he knows! but now I’m getting even Idris trained to call me Dillan, though it’s under protest!’

‘What part of Wales do you come from?’ I said.

‘Oh, I only come from a small town. Swansea.’

Whereas I had previously felt myself to be the most naive member of a group otherwise composed of sophisticated, bohemian intellectuals, I now felt I had, vis-à-vis Dylan Thomas, at any rate, an advantage in being a Londoner. ‘I should have thought Swansea was a large town,’ I said. ‘I was near there all last summer. If you had been to the theatre at Porthcawl you would have seen me on the stage!’

‘No, I’m afraid I didn’t’ he said. ‘What a pity!’

Giving the conversation a turn he did not expect, I said, ‘Have you ever been down a mine?’

‘No.’

‘I have!’ I explained triumphantly. ‘Near Crumlin. I once played a January date in the Rhondda. Or more exactly the Ebbw Vale.’ I told him how I had persuaded the men at a pit to take me down the shaft, and how, having arrived at the bottom, I was given a lamp to hold and escorted along a passage which had been hewed through the coal to a point where it became so low that one would have had to proceed on hands and knees. I was shown a fault seam, which I felt with my fingers.

‘You have seen something in Wales which I haven’t!’ said Dylan. He explained that his home was some distance from the mining regions. He described the part of Swansea where he lived, with a detail I cannot now recall, except that it sounded salubrious and agreeable. His father was Senior English Master at the Grammar School. ‘Living where I do one doesn’t really see anything of all that,’ he said, with reference to my allusion to the coal mining (and depressed) areas. ‘Idris comes from the Rhondda,’1 he said. ‘I haven’t been into those areas.’ As though he had been slightly shamed by my adventure, he added, ‘Perhaps I ought to have done.’

‘It’s because you live there that you wouldn’t think of it,’ I said. ‘When one is touring one feels one must see everything in case one never comes again. When I was sixteen, my mother and I made a tour of Italy, Pisa, Rome, Naples, Capri, and back through Perugia, Florence and Milan. We felt we had to go into everything, even the smallest church we passed on any street. We realized we had never “done” London half as thoroughly because we took it for granted.’

I have no ‘outrageous’ sayings of Dylan Thomas to record. His conversation with me was perfectly drawing-room and unexceptional. I remember him as a polite young man. Friendly, but not at all presuming.

He told me the origins of the circle of which I now formed part. ‘First one and then another of us found our way to Vicky’s through entering into correspondence with him or something like that, and so a circle grew up around Vicky. We’re all very fond of Vicky.’ He explained that, ‘always reading each other’s names in print we began to wonder what the ones whom we hadn’t seen were like.’ So they had had the idea ‘of sending out circulars to everybody who was a contributor. He thought it had brought in some interesting people. ‘Well, it has brought you!’ Perhaps one could name some kind of a regular thing of it. ‘The only thing I don’t like is the name Zoists!’ he said.

I laughed and said, ‘It does sound a bit like protozoa, zoophytes and zoids!’

Dylan pulled a funny face.

‘We’re always called “Vicky’s children”,’ said Dylan. ‘It’s a bit sentimental, but I don’t think we shall ever be called anything else.’

It had been at the back of my mind while he was speaking that his name, as he had spelled it out, was one which I had read in the Sunday Referee in a context more important than that of the weekly prizes. I had not taken the paper regularly before I joined the circle, or I would have known the whole build-up. I said, ‘Aren’t you the winner of a big prize? I believe you’re one of the distinguished people here!’

‘It was through Vicky and the Sunday Referee that a book of my poems has been published,’ he said. He explained that a prize was offered twice yearly, part of which consisted in the publication of the winner’s poems in book form. ‘The first was awarded to Pamela Hansford Johnson. She isn’t here tonight. I was given the second of them.’ He said that Vicky had helped him pick out what he thought were the best of the poems he had written.

‘What’s it called?’

‘Just 18 Poems. It was published just before Christmas, and I think it’s doing quite well.’ He added, ‘I’m very grateful to Vicky. It’s a big thing for me. One’s first book is the most difficult to get published. Everyone says so. Now that I have one book published, it should be easier to get the next accepted, perhaps by an ordinary firm.’

My sentiment for Vicky was already so strong that I was slightly shocked.

Dylan Thomas saw it. ‘Vicky doesn’t expect us to stay with him!’ he said. ‘This is a nursery school from which we are expected to go out into the world. When we can get published elsewhere nobody is more pleased than Vicky!’

Just then the moment for which we had been waiting arrived. The door from the inner part of the house opened and our hosts came out to join us.

Vicky came straight up to Dylan and me. I did not know which of us the distinction was meant for but it gave me joy. He stood by my chair, looking down on us beamingly, and said to Dylan, ‘You’re entertaining this little lady?’

Dylan said, ‘I’ve been telling her something of the history of the Poet’s Corner.’

*********************************

Laugharne,

Carmarthenshire,

Wales

19 June 1940

Dear Miss Fuller

I haven’t heard anything from Vicky and Runia for years, until about a fortnight ago.

Then Pamela Johnson wrote to tell me that Vicky had just died. I was very grieved to hear it; he was a sweet, wise man. Runia’s address is 84, Boundary Road, NW8. At least, I suppose she is still there. I wrote her a letter, but I haven’t had a reply yet; probably she’s too sad to write.

Yours sincerely

Dylan Thomas

#occult #literarymodernism #aleistercrowley #victorneuberg #poetry #magick #mandrakeofoxford